A Post on Tournament Designs

The Problem

When hosting our annual Matzah Hunt event, we wanted to come up with a cool and unusual way of picking teams. We decided that we wanted each participant to complete each puzzle only once and to complete each puzzle with a different partner. Here are the precise details of the problem:

There are 12 participants, 6 puzzles and 6 (20-minute) rounds. Teams of 2 will attempt to solve each puzzle each round. We want to create teams of 2 such that every participant attempts each puzzle one time with a new partner each time.

Apparently this type of problem falls into the arena of tournament designs which we were not familiar with. These types of problems come up all the time when scheduling sports team games- where you have a fixed number of teams, time slots, and courts. Our problem can be viewed as 12 teams, 6 courts and 6 time slots, where we would like each team to play exactly once on each court, each time to a different opponent.

We figured this should be a solvable problem and first tried to brute force a solution before we quickly realized that this was a much more challenging problem than we first expected.

A Simpler, Smaller, Easier Problem

A simpler, smaller, and easier problem than the one above is called a Balanced Tournament Design, BTD(m). Here, every team plays only once in each round, and every team plays on each court at most two times.

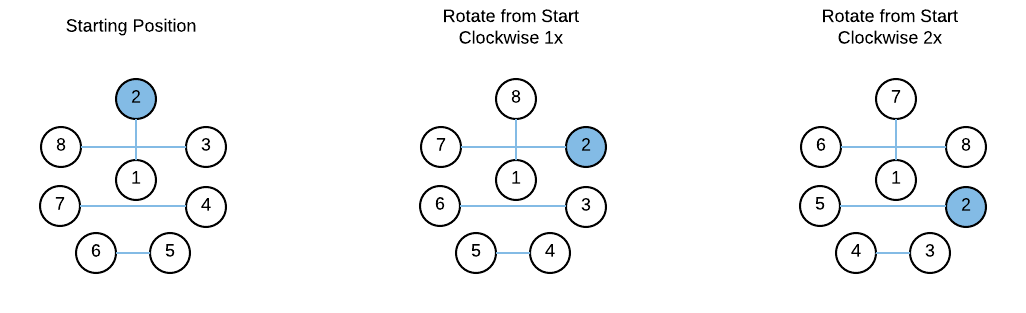

Suppose we have an even number of teams, \(n\), and \(m=n/2\) courts. We first construct a round-robin cyclic schedule for these \(n\) teams. When \(n=8\) the first 3 rounds of the round-robin cycle construction looks like this:

Figure: Typical Cyclic Tournament Construction with n=8

Each of the three graphs represents a round. The lines in this diagram represent teams playing one another in that round. The diagram only shows rounds 1, 2, and 3, but further rotating clockwise will produce rounds 4 though 7. In table format, the complete cyclic schedule for \(n=8\) is

| Round | Court 1 | Court 2 | Court 3 | Court 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1,2) | (3,8) | (4,7) | (5,6) |

| 2 | (1,8) | (2,7) | (3,6) | (4,5) |

| 3 | (1,7) | (8,6) | (2,5) | (3,4) |

| 4 | (1,6) | (7,5) | (8,4) | (2,3) |

| 5 | (1,5) | (6,4) | (7,3) | (8,2) |

| 6 | (1,4) | (5,3) | (6,2) | (7,8) |

| 7 | (1,3) | (4,2) | (5,8) | (6,7) |

So now we have each team playing every other team such that each team is only playing one time per round. The issue now is that Team 1 is only playing on Court 1 and all other teams are playing 2 times on each of the other courts. We would like the court assignments to be as balanced as possible. Since Teams 2-7 play on each of courts 2, 3, and 4 exactly 2 times, you might be thinking that we could swap these duplicates with the (1,X) on court 1. You would be correct.

Specifically, Hasselgrove and Leech (1977) describe the algorithm:

- Take Round 1 to be the same Round 1 from the typical cyclic algorithm (Round 1 in table above and the “Starting” graph in the Figure above).

- Subsequent rounds are obtained by rotating the graph clockwise \(n/2-1\) times. Alternatively, you can take the typical cyclic table (table above) and start at Round 1, count \(n/2-1\) rounds down, and record that round as the next Round. You continue this process until all the rounds have been chosen. Note: when you reach the last row, cycle back up to the first row and continue. In our example, the Rounds 1-7 correspond to the old Rounds 1,4,7,3,6,2,5. The new table looks like:

| New Round | Court 1 | Court 2 | Court 3 | Court 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1,2) | (3,8) | (4,7) | (5,6) |

| 2 | (1,6) | (7,5) | (8,4) | (2,3) |

| 3 | (1,3) | (4,2) | (5,8) | (6,7) |

| 4 | (1,7) | (8,6) | (2,5) | (3,4) |

| 5 | (1,4) | (5,3) | (6,2) | (7,8) |

| 6 | (1,8) | (2,7) | (3,6) | (4,5) |

| 7 | (1,5) | (6,4) | (7,3) | (8,2) |

- With this modified table, we make the following swaps: a. For Rounds \(R=1,...,n/2-1\), swap Courts \(1\) and \(R+1\) b. For Rounds \(R=n/2,...,n-2\), swap Courts \(1\) and \(n-R\) c. For Round \(R=n-1\), do not swap

Below is the new table. Here, the bolded pairs have been swapped.

| New Round | Court 1 | Court 2 | Court 3 | Court 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (3,8) | (1,2) | (4,7) | (5,6) |

| 2 | (8,4) | (7,5) | (1,6) | (2,3) |

| 3 | (6,7) | (4,2) | (5,8) | (1,3) |

| 4 | (3,4) | (8,6) | (2,5) | (1,7) |

| 5 | (6,2) | (5,3) | (1,4) | (7,8) |

| 6 | (2,7) | (1,8) | (3,6) | (4,5) |

| 7 | (1,5) | (6,4) | (7,3) | (8,2) |

Our modification is complete and we have found the best balance for this tournament. Recall that I mentioned that this was the procedure for an even number of teams. You can use the exact same procedure when n is odd with only a slight modification. If n is odd, complete the algorithm with \(n+1\) teams, and say that every time Team X plays Teams 1, Teams X gets a bye-week (a week when they don’t play).

When the Algorithm Works

This algorithm works when the number of teams \(n\) satisfies \(n\equiv \{0, 2\} \pmod 3\).

Puzzles and Partitions

This is all very interesting but does not get at the solution we need exactly. Again, our problem can be viewed as 12 teams, 6 courts and 6 time slots, where we would like each team to play exactly once on each court, each time to a different opponent. This would require what is called a Partitioned Balanced Tournament Design, PBTD.

A PBTD is a BTD where each team plays on each court exactly once in the first and last \(n/2\) rounds.

We don’t really care about the last \(n/2\) rounds for our puzzle problem since there we only want 6 (n/2) rounds, but the first \(n/2\) partition will be a nice solution.

According to Lamken in 1987 and 1996, there exists PBTD’s for more than 3 courts, with possible exceptions of 18, 22, and 30 courts.

The Challenge

It is really hard to construct PBTDs. We know they exist, but solving for them requires a substantial amount of Combinatorial Analysis. I was lucky enough to stumble upon a great thread that solved our problem. References are given at the end of the post.

But the final solution for our puzzle problem is given in the table below:

| Round | Puzzle 1 | Puzzle 2 | Puzzle 3 | Puzzle 4 | Puzzle 5 | Puzzle 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1,2) | (3,4) | (5,6) | (7,8) | (9,10) | (11,12) |

| 2 | (3,7) | (1,10) | (4,12) | (9,11) | (6,8) | (2,5) |

| 3 | (8,11) | (6,12) | (3,10) | (2,4) | (5,7) | (1,9) |

| 4 | (6,9) | (5,8) | (2,11) | (3,12) | (1,4) | (7,10) |

| 5 | (4,10) | (7,11) | (8,9) | (1,5) | (2,12) | (3,6) |

| 6 | (5,12) | (2,9) | (1,7) | (6,10) | (3,11) | (4,8) |

Here we have participants numbers 1 through 12. Notice that every participant gets to attempt every puzzle, each time with a different partner. Additionally, no one attempts more than one puzzle in a round.

References and Further Reading

There is a wonderful thread on the Round Tobin Tournament Scheduling community, which it hosted by Richard A. Devenzia. There, Ian Wakeling posts linked to his Excel file and Richard’s website that computes tournament designs. This is very helpful and definitely worth a look.

Here is the link, on the same website, slightly different thread, where Ian gives the PBTD for 10, 12, and 14 teams that solved the PBTD.

Dinitz, Jeffrey H. n.d. “Designing Schedules for Leagues and Tournaments.”

Haselgrove, Jenifer, and John Leech. 1977. “A Tournament Design Problem.” The American Mathematical Monthly 84 (3): 198–201.

Lamken, E R. 1990. “Generalized Balanced Tournament Designs.” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 318 (2): 473–90.

Mendelsohn, E, and P Rodney. 1994. “The existence of court balanced tournament.” Discrete Mathematics 133: 207–16.

Shellenberg, P. J., G.H.J. van Rees, and S.A. Vanstone. 1977. “The existence of balanced tournament designs.” Ars Combinatoria 3: 303–18.